Key components of interdisciplinary learning

There are several levels to interdisciplinary learning: students may experience it by taking a class that combines several subjects, or be a part of a program that is intentionally interdisciplinary, such as the Bren school, or even attend a liberal arts college where they become interdisciplinary through the nature of their coursework. No matter the level a student is at in their education, there are patterns that emerge that foster interdisciplinarity in their learning. From our own personal experiences, talking to established faculty, and the journal papers below, we found that these patterns include when students go outside of their comfort zone and interact with other students from different backgrounds in both formal and informal settings, it creates an invaluable experience that leads to interdisciplinarity in a student.

Student Opinions on Interdisciplinarity and Fostering Student Buy-In

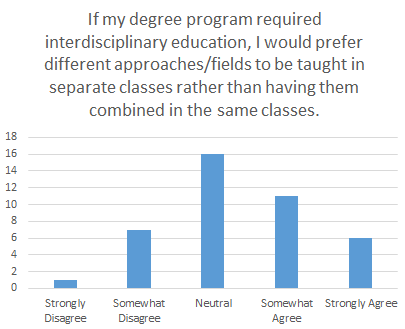

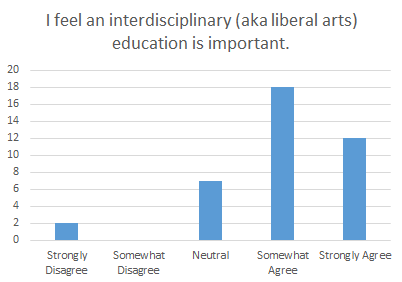

In a survey of a UCSB general education natural history course, with a combination of STEM and humanities students, we found that students would rather have separate subjects taught in separate courses (Fig. 1) despite valuing an interdisciplinary/liberal arts education overall (Fig. 2). Students felt that they would rather have strong backgrounds in each separate subject before making the connections between them, however, being in this class that combined history and natural science introduced them to the potential of interdisciplinary learning and the importance of being well-rounded.

Several studies of interdisciplinary education programs including a sciences and engineering program (Gero 2017), engineering and English (Wojahn, Riley, & Park, 2004), and sustainability (Feng 2012), also found that students were hesitant at the outset of these courses.

Several of our faculty interviewees would likely be unsurprised upon reading the findings of the above researchers:

If reality does not divide itself into discrete disciplines, as Drs. Porter and Awramik believe, then it stands to reason that students would appreciate this sort of education because it is a fuller and more accurate illustration of what they are trying to learn. If academics and researchers believe that interdisciplinarity is the reality, then education must in some way reflect that. Sharing this ‘true’ interdisciplinary reality with the student(s) helps break down the barriers between teacher and student making classroom learning a more “authentic” learning (borrowing the term from Brown, Collins, & Duguid.’s [1989] authentic activity).

For graduate students, our interviewees have more faith in students’ ability to create interdisciplinary collaborations based on their own experiences and interests.

On Master’s students in an interdisciplinary environmental program:

According to our interviewees, opportunity to interact with students from other disciplines, rather than forcing them to interact via a structured class as with undergraduates, is key to fostering interdisciplinarity among graduate students.

References

- Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Research, 18(1), 32–42.

- Feng, L. (2012). Teacher and student responses to interdisciplinary aspects of sustainability education: what do we really know? Environmental Education Research, 18(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.574209

- Gero, A. (2017). Students’ attitudes towards interdisciplinary education: a course on interdisciplinary aspects of science and engineering education on interdisciplinary aspects of science and engineering education. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(3), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2016.1158789

- Wojahn, P., Riley, L. A., & Park, Y. H. (2004). Teaming engineers and technical communicators in interdisciplinary classrooms: working with and against compartmentalized knowledge. In International Professional Communication Conference (pp. 156–167). Minneapolis, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/IPCC.2004.1375291